Birth and Early Life in Flat Lick, Kentucky

Susan Elizabeth Tinsley, fondly known as Eliza to her family, was born in February 1849 in Flat Lick, Knox County, Kentucky, to Warrick Tinsley and his first wife, Mary, whose maiden name was likely Goins. This assumption stems from the 1850 census record that lists a 13-year-old named Francis Goins living with Warrick and Mary, suggesting a familial connection. Susan grew up during a complex and tumultuous time when her family was transitioning from enslavement to freedom.

Flat Lick, Kentucky, during this time was a small, rural community known primarily for its agricultural activities. Unlike larger plantations, the Tinsleys likely had a modest setup, as their enslaver, William D. Tinsley Sr., did not have substantial wealth. **Susan Elizabeth Tinsley’s Siblings and the Tinsley Family’s Fight for Freedom**

Susan Elizabeth Tinsley was born into a family with a complex history marked by both the trauma of enslavement and the strength required to fight for their freedom. She was one of several children born to Warrick Tinsley and his first wife, Mary, in Flat Lick, Knox County, Kentucky, around February 1849. Susan’s siblings, both full and half-siblings, played integral roles in the Tinsley family’s story of struggle, survival, and eventual emancipation.

Susan had two older full siblings, Charles and Fanny Tinsley. Charles, born around 1840, was likely the oldest and would have been exposed to the harsh realities of slavery during his early years. Fanny, born around 1848, was also a full sibling who shared in the early experiences of bondage. Alongside these siblings were several others whose relationships were either full or half: Bammer (born around 1852), Patsa (often referred to as Patsy or Martha, born around 1854), and Harriet (born around 1856). Each of these siblings, along with those born later—Merrica (America, born around 1858), Elen (born around 1861), Hannah (born around 1864), Mary (born around 1866), and Catherine (born around 1869)—were born into a life shaped by the heavy burden of their family’s fight for freedom.

The Tinsley family’s battle for freedom was both grueling and significant. The family’s matriarch, Fanny Tinsley, Susan’s grandmother, was brought to the household of William D. Tinsley Sr. around 1812, at about the age of seventeen. Fanny was recorded as Black, while her children were consistently listed as Mulatto in official records—a fact that strongly suggested William D. Tinsley Sr. was their biological father, especially since there were no other Black men in his household. This assumption was further supported by the language in William Tinsley’s will, which specifically mentioned Fanny and all her children by name and stated that they were to be freed upon his and his wife’s death. This provision in his will, however, was not honored by his heirs, who resisted the directive, sparking a prolonged legal battle that lasted six years.

The Tinsley family’s fight for freedom became a significant legal struggle in Kentucky, reflecting the broader conflicts over emancipation and rights in the United States. Fanny and her children, including Warrick, Susan’s father, fought tirelessly in the courts against William Tinsley Sr.’s heirs, who did not wish to fulfill his wishes. The case was a grueling process that brought the family face to face with the stark reality of a society unwilling to relinquish its grip on those it viewed as property. Eventually, the court ruled in favor of Fanny and her children, granting them their freedom. However, this freedom was not unconditional; the judge’s ruling included a requirement that the newly freed individuals be employed upon receiving their freedom, a stipulation likely intended to ensure they did not become a perceived burden on the community.

The outcome of the court case was a monumental victory for the Tinsley family, symbolizing their transition from enslavement to freedom. Yet, it also came with the painful acknowledgment of their mixed-race heritage—a direct result of the exploitation of their matriarch. The Tinsleys’ emancipation laid the groundwork for future generations, such as Susan Elizabeth Tinsley, to pursue lives marked by a greater degree of independence and opportunity. The resilience shown by the Tinsley family in both the courtroom and daily life became a defining characteristic that would shape Susan and her siblings’ paths in the years following the end of enslavement.

Susan’s life, shaped by this legacy of resistance and survival, would go on to reflect the strength and determination instilled by her family’s fight for freedom. Her upbringing in a family that fought against all odds to secure their freedom provided a foundation that enabled her to navigate a post-Emancipation America with a sense of agency and ambition that was rare for Black women of her time.

Growing Up Free and Moving to Kansas

Born free as a result of this court case, Susan would not have experienced the trauma of enslavement first-hand. However, she grew up understanding the value of freedom, as it had been hard-won by her family. In 1869, at the age of 19, Susan left her father’s home in Flat Lick and traveled to Leavenworth, Kansas. Contrary to some family beliefs, she likely did not leave during the Civil War, as that would have meant traveling hundreds of miles in the middle of a war zone. Instead, she moved west in a post-war environment, seeking work and new opportunities.

Employment with the Custers

After the Tinsley family’s successful legal battle for freedom in Kentucky, Susan Elizabeth Tinsley’s life took a significant turn when she moved to Leavenworth, Kansas, around 1869. This move, made when Susan was about 19 years old, was likely driven by the search for better opportunities and the desire to establish herself in a new environment away from the constraints and societal memory of the South’s deeply entrenched racial hierarchy. Leavenworth was a growing city at the time, with a bustling military presence, which offered new economic opportunities, especially for African Americans looking to carve out lives in the post-Civil War era.

The decision to move to Kansas was a strategic one. As a free state, Kansas had been a beacon for African Americans, both before and after the Civil War. Leavenworth, in particular, was a hub of activity due to its position as a military outpost and its developing infrastructure. It would have presented more economic and social opportunities than the heavily segregated and violent environment of the South. Susan likely sought to take advantage of the expanding job market and greater safety in a Northern state that, at the time, had a slightly more progressive stance toward African Americans compared to the Southern states.

It was in Leavenworth that Susan’s life intersected with that of the Custers—General George Armstrong Custer and his wife, Elizabeth Bacon Custer. While the exact circumstances of how Susan came to work for the Custers are not entirely clear, it is likely that her arrival in Leavenworth and the bustling nature of the military town placed her in a position to be hired by them. The Custers were well-known in military and social circles, and Susan might have been recommended or sought employment with them through local connections or word of mouth. At the time, the Custers were looking for household help; Elizabeth Bacon Custer had recently dismissed their previous cook, Eliza Brown Davison, who had returned to Ohio. This opening would have provided an opportunity for Susan to step in as a maid and, eventually, a cook.

Working for the Custers would have been considered a relatively prestigious position for an African American woman in the 1860s, given the high profile of the family in military and political circles. Susan’s employment in their household would have involved a range of domestic duties, from cooking to general housekeeping. During this time, she would have witnessed the complex social dynamics of military life and likely the conversations surrounding Custer’s military strategies and expeditions.

It’s also possible that Susan’s skills, personality, or reputation for hard work made her an attractive hire for the Custers. Elizabeth Bacon Custer was known for her strong-willed nature and high expectations of her staff, and it’s likely that Susan’s abilities in maintaining the household met these standards. This employment marked a pivotal point in Susan’s life, providing her with experience in managing a prominent household, which would later influence her entrepreneurial ventures in mining speculation and running a boarding house in Helena, Montana.

Thus, Susan’s move to Kansas was not just a geographical shift but a significant leap toward independence, economic stability, and a stepping stone to further opportunities. It was a decision rooted in ambition and the pursuit of a better life, reflecting the spirit of resilience passed down from her family’s hard-won freedom.

Susan found employment with General George Armstrong Custer and his wife, Elizabeth Bacon Custer, in November 1869. She began her service as Mrs. Custer’s maid and later became the family’s cook, who fondly named her Eliza. Her granddaughters recounted how Susan was a source of comfort and calm to “Miss Libbie” (Elizabeth Custer), especially when she fretted over General Custer’s safety during his Indian war campaigns. “Don’t take on so, Miss Libbie,” Susan would say. “Nothing’s going to happen. The General’s all right.”

While employed by the Custers in Leavenworth, Kansas, Susan Elizabeth Tinsley became known for her cooking, preparing meals that reflected both her African American heritage and the influences of the frontier environment she was a part of. According to family recollections shared by her granddaughters in later newspaper interviews, Susan prepared hearty, comforting dishes that were well-suited for both the household and the soldiers. She often cooked meals that would have been common in both African American and Southern kitchens, including fried chicken, cornbread, collard greens, and stews made with locally available ingredients. These meals were substantial, aiming to sustain the energy levels of the Custers and their guests, and to meet the expectations of a high-profile household.

Her granddaughters recalled that Susan had a natural talent for cooking and could make the most of simple ingredients, a skill that would have been highly valued in a military household where rations and supplies might sometimes be limited. She was particularly skilled in creating savory, filling dishes that could feed many and still taste delicious. Her recipes likely involved a blend of the flavors she grew up with in Kentucky and those she adapted to suit the preferences of the Custers and their social circle. This mix of flavors, influenced by African American culinary traditions, would have set her cooking apart, adding a unique touch to the dining experiences in the Custer household.

Recipes and Cooking Style: Eliza’s cooking was well-regarded. She had her own unique recipes that she would prepare for the Custers:

Goose: She would singe and clean the goose, then wash and rinse it inside and out. After drying it thoroughly, she stuffed it with mashed potatoes, chopped turnips, apples, boiled onions, salt, sage, and pepper. The goose was then placed in a pan covered with slices of fat-side pork and roasted in a hot oven for three-quarters of an hour. She would baste the goose as it cooked and serve it with a gravy made from the pan drippings.

Hamburger Steak: Eliza prepared hamburger steak by pounding a slice of round steak, removing any fibrous parts, and frying it with onions. She would then simmer the onions in the gravy. This dish was typically served with salt, pepper, and accompanying vegetables.

Vegetable Dishes: She was known for her mixed vegetable combinations and side dishes, seasoned heavily with onion, sage, and pepper. These would include chopped turnips, apples, boiled onions, and sometimes a mixture cooked with fat pork.

One of her granddaughters fondly remembered how Susan, even as she managed her responsibilities as a cook, maintained a vibrant and resilient spirit. She was known to be assertive yet kind, commanding respect in the kitchen while caring deeply for those she cooked for. The recollections from her granddaughters also highlight her strength and grace under pressure, traits that were necessary given the Custers’ demanding social life and Elizabeth Bacon Custer’s reputation for having high expectations of her household staff.

During this period, Susan was also caring for a young boy named Henry Saunders, who was likely either her biological son or a child she had taken in from a nearby family. Henry later took the surname “Mundy” after Susan’s husband, Lafayette Mundy, whom she married in 1873.

The stories shared by Susan’s granddaughters reveal a woman who left a lasting impression not only on those she worked for but also on her family, who remembered her as a figure of fortitude and skill, capable of thriving in environments that demanded both adaptability and determination. The Custers, particularly Elizabeth Bacon Custer, were known for their strong personalities, and it is a testament to Susan’s character that she navigated these dynamics with poise, making a mark through her cooking and presence. These anecdotes provide a personal glimpse into Susan’s life during her time with the Custers, highlighting the depth of her character beyond her roles and responsibilities.

Marriage to Lafayette Mundy and the Move to Texas

During Susan Elizabeth Tinsley’s time with the Custers, General George Armstrong Custer was deeply involved in the United States military’s campaigns against Native American tribes in the western territories, often referred to as the Indian Wars. These campaigns, conducted during the post-Civil War era, were primarily focused on forcibly removing Native American tribes from their ancestral lands, confining them to reservations and killing the rest.

This policy was driven by the government’s desire to open these lands to white settlers and miners. This process was part of the broader U.S. policy known as “Manifest Destiny”, which asserted that Americans were destined to expand across the continent. The military operations aimed to eliminate Native resistance, which resulted in devastating consequences for Native communities, including the loss of life, land, and cultural autonomy.

As a cook in the Custer household, Susan would have likely been aware of the tensions and the brutal reality of these campaigns. She may have heard discussions about military strategy and reports of battles and skirmishes. General Custer was known for his aggressive tactics and was involved in several significant battles against Native American tribes. One of the notable conflicts just before Susan’s time with the Custers was the Battle of Washita River in November 1868, where Custer led the 7th Cavalry in a surprise attack on a Cheyenne village in present-day Oklahoma. The attack resulted in the death of many Cheyenne, including women and children, and the destruction of the village. This battle was marked by its brutality and was a stark representation of the violence of the Indian Wars.

It was during this period that Susan likely met Lafayette Mundy, a Buffalo Soldier. Buffalo Soldiers were African American soldiers who served on the western frontier, primarily tasked with supporting the U.S. Army’s campaigns against Native American tribes. Lafayette served with the 4th U.S. Colored Cavalry during the Civil War and continued his military career in the post-war period as this was likely the best paying employment for a gifted horseback soldier.

He was of Cherokee, Mohawk, Dutch and Black ancestry, while she claimed to be of Cherokee and African American.

As a Buffalo Soldier, Lafayette would have been involved in various military engagements, escort duties, and fort maintenance tasks aimed at protecting white settlers and expanding American interests in the West. The work of the Buffalo Soldiers, though controversial, provided African American men like Lafayette with stable employment and a chance to serve in the military, despite the irony of fighting against other oppressed groups. They were named “buffalo soldiers” by the natives they fought as a testament to their bravery and toughness.

Susan and Lafayette’s paths likely crossed because of the interconnected lives of African Americans in military and service roles on the frontier. Both being part of a segregated military and social environment, Susan and Lafayette would have had common experiences and challenges. Their connection would have been strengthened by their shared struggle for survival and advancement in a country that often marginalized them. Their relationship would have grown from these shared experiences, and they eventually married in 1873, eventually leaving the Custer’s employ in 1875.

General George Armstrong Custer met his death on June 25, 1876, at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in Montana Territory. Known as “Custer’s Last Stand,” this battle saw Custer and his 7th Cavalry overwhelmed by a coalition of Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors. Outnumbered and outmaneuvered, Custer and all of his men were killed, marking one of the most infamous defeats for the U.S. Army during the Indian Wars and a significant victory for the Native American forces defending their land.

Life in Old Mexico and the Birth of Thaddeus

After leaving the Custers’ employ in 1875, Susan and Lafayette moved to Chihuahua, Mexico.

This move coincided with the Salt Wars, a conflict between local Mexican-American communities and Anglo-American businessmen over the rights to salt beds, which were essential resources for the region. As a Buffalo Soldier, Lafayette’s role during this conflict was as an interpreter for the bureau of immigration would have utilized his skills honed during the Civil War, serving the U.S. military’s aim to control and displace Native populations and maintain order in contested territories.

It was amidst this conflict that their son, Thaddeus Mundy, was born on March 6, 1877, in Chihuahua. The birth of Thaddeus during such a turbulent period highlights the challenges Susan and Lafayette faced as they navigated life on the frontier, marked by both personal growth and the harsh realities of post-Civil War America. Their decision to move to Mexico during the Salt Wars reflects their resilience and adaptability, constantly seeking better opportunities and safety for their family amidst a backdrop of ongoing violence and social upheaval.

Return to Kansas and Later Life in Montana

By 1880, Susan and her family returned to Leavenworth, Kansas. Lafayette had left the army by then and worked as a coal miner. Over the next decade, Susan and Lafayette’s marriage began to fall apart. Records suggest they separated before 1889, and Susan, now referring to herself as Elizabeth Mundy, relocated to Helena, Montana, where she would live for the next several decades. Lafayette went on to stay in Kansas and get remarried.

In Helena, she operated a boarding house and became an entrepreneur in mining speculation. Notably, Susan, along with Margaret Dooney, located the Winona Lode in 1893, marking her as a pioneering woman in an industry where female ownership of mining claims was extremely rare. Susan’s ambition to enter mining was highly unusual for a woman of her time, let alone a Black woman.

Life as Elizabeth Miller and Commitment to Montana State Hospital

In Helena, Susan sometimes went by the name Elizabeth Miller, although no marriage records have been found to confirm a marriage to a man named Henry Miller. She was listed as a widow under this name in the 1914 and 1915 city directories, still residing on Warren Street. The reasons for these changes in identity remain unclear, but they reflect her complex personal life and the possible need to navigate societal norms of the era.

Unfortunately, as she aged, Susan began experiencing hallucinations and delusions, leading to her commitment to the Montana State Hospital for the Insane in Warm Springs, Montana, in July 1918. She remained there until her death on February 19, 1923, from fibroid phthisis, a form of tuberculosis, and pneumonia.

Legacy and Family Recollections

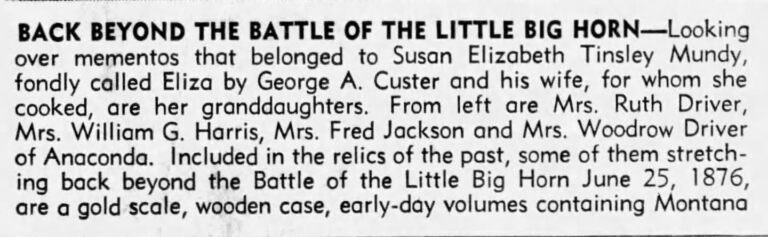

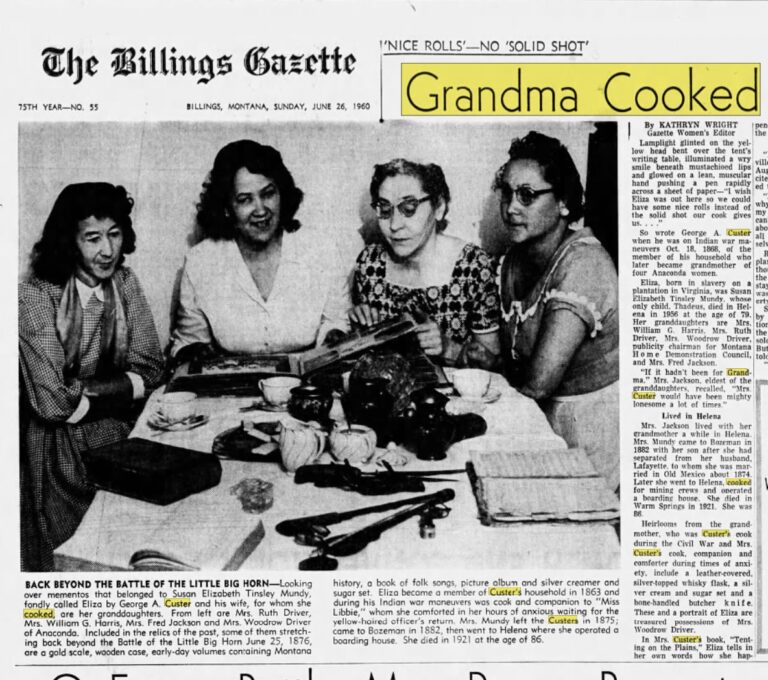

In the summer of 1960, the stories of Susan Elizabeth Tinsley Mundy—fondly remembered as “Eliza” by the Custer family—came alive once more through the voices of her granddaughters. On June 26, 1960, *The Billings Gazette* published an article titled “Grandma Cooked for Custer,” where four granddaughters of Eliza—Mrs. Ruth Driver, Mrs. William G. Harris, Mrs. Fred Jackson, and Mrs. Woodrow Driver—shared cherished memories and anecdotes of their grandmother’s extraordinary life. The article described how Eliza, born Susan Elizabeth Tinsley, had worked as a cook and companion for General George Armstrong Custer and his wife, Elizabeth “Libbie” Custer, during the years leading up to 1875.

Eliza’s granddaughters spoke with pride as they recounted the unique legacy she left behind. They remembered how Eliza, a woman who had once fled a southern plantation to “find out what this liberty’s all about,” became an integral part of the Custer household. The granddaughters recalled how their grandmother would calm Mrs. Custer’s fears during these anxious times. When Mrs. Custer expressed concern for her husband’s safety, Eliza would reassure her, saying, “Don’t take on so, Miss Libbie. Nothing’s going to happen. The General’s all right.”

The article painted a vivid picture of Eliza’s culinary expertise, detailing some of her signature dishes that she prepared for the Custers. The granddaughters also reminisced about the heirlooms and mementos Eliza left behind. Among the treasured items were cookbooks filled with her recipes favored by Custer, a gold scale, a wooden case, an old book of folk songs, a picture album, and a silver creamer and sugar set. These relics became cherished family keepsakes, linking the present generations to Eliza’s storied past.

The articles in *The Billings Gazette* and other local newspapers brought to life the vivid tales of a woman who had navigated a complex period of American history with grace and determination. Eliza’s story was not only about her role as a cook for the Custers but also about the broader historical context she lived in—her journey from the South in pursuit of freedom, her life as a Black woman in post-Civil War America, and her legacy that continued to inspire her descendants. The granddaughters’ memories, shared with the world through these newspaper stories, ensured that Eliza’s life and spirit would not be forgotten.