Head's up! Voting for the next Virtual Family Reunion is now open. Cast your vote!

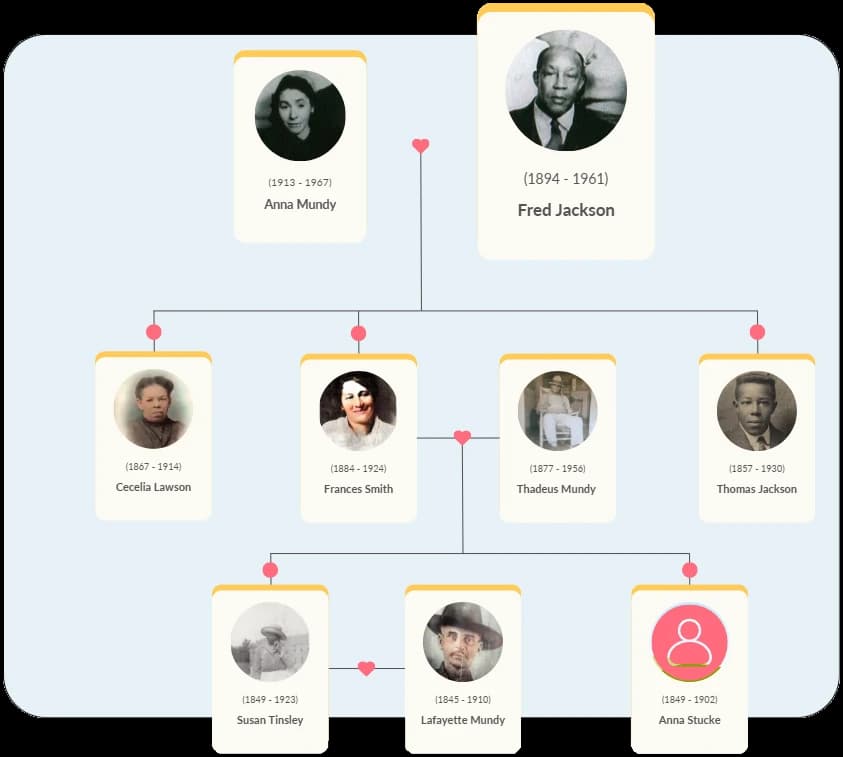

Featured Ancestor

Susan Tinsley

Join the journey of rediscovering your roots and building stronger family bonds. From fun quizzes to newsletters and virtual reunions, stay connected and celebrate the legacy that unites us all.

Journey Through Time

NEXT

Turn the dial for the next event

Expedition from Yorktown to Matthews County

October 4–9, 1863

A Gallery of Memories

Join the journey of rediscovering your roots and building stronger family bonds. From fun quizzes to newsletters & virtual reunions, stay connected and celebrate the legacy that unites us all.

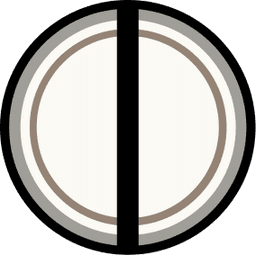

Get Ready for The Jackson Family Family Reunion!

Help us pick the best date for our next virtual get-together.

Vote for the Next Reunion!

Loading poll...

VOTING CLOSES IN

Make sure you cast your vote!

More Family Members

Join the journey of rediscovering your roots and building stronger family bonds. From fun quizzes to newsletters & virtual reunions, stay connected and celebrate the legacy that unites us all.

Anselme Hatfield

Anselme Hatfield's story crosses borders and legacies- born in revolutionary New York and laid to rest in Acadian Nova Scotia, he helped seed a family rooted in resilience and heritage.

Read MoreMarie-Marguerite Mius D’Entremont

Marie-Marguerite Mius D'Entremont carried the legacy of Acadian resilience - born in Argyle and rooted in Clare, she helped weave a family history that bridged cultures and centuries.

Read MoreJoseph Sambo Cromwell

Joseph Sambo Cromwell's life charts a powerful arc—from the shores of Africa to Black Loyalist refuge in Nova Scotia, he left an enduring legacy of strength, survival, and freedom.

Read MoreSusan Elizabeth Tinsley

Susan Elizabeth Tinsley lived through a century of American transformation- from antebellum Kentucky to frontier Montana - carrying with her the strength of generations.

Read MoreFrances Leona Smith

Frances balanced the trials of frontier womanhood and motherhood ”her life, woven through love, resilience, and loss, shaped the roots of generations in Montana's rugged terrain.

Read MoreLafayette Mundy

Lafayette Mundy's life traced the arc of a transformative century - fighting in the Civil War, raising a family through Reconstruction, and serving as a steadfast figure in the African American journey through postwar America.

Read More